THE IRISH DILEMMA

As we saw, Winston Churchill’s earliest memories are of Ireland and Dublin.

We also now know the real reason why he had to leave merry old England, before he was even two years old.

We have seen that his father had a monumental row and serious quarrel with the Prince of Wales and future King Edward VII, so that his grandfather had to accept the offered position of ViceRoy of Ireland.

Randolph had to also accept the position of his father’s secretary, because the previously agreed upon ‘Arrangement’ of covering up for the Princely Concubine and protecting the ‘Royal Bastards’ in a nice warm and cozy, family environment, did not suit his tastes anymore, or did not satisfy Randolph’s financial interests any longer, and he threatened the Prince with the publication and exposure of some of his correspondence and personal letters about this matter.

It was then that wiser heads prevailed, and Winston Churchill’s Grandfather ‘The Duke of Marlborough’ immediately stepped into the breach of decorum, and dragged his son Randolph to Dublin. Of course his son’s new bride and fresh grandson, had to come along, as the whole family fled the famed Victorian Royal angst to emerald green Ireland. It turns out that in order to keep-up appearances, this family transfer was effected because this is where the Duke of Marlborough had ostensibly accepted the position of “Viceroy of Ireland.” The old Duke, did this in a haste, in order to remove his impulsive son Randolph, from the looming storm where he had invoked the serious wrath of the Crown, of Queen Victoria, of the Prince of Wales himself, and of the whole of the Court of St James, and indeed of the whole of the English Aristocracy, and London Society.

They were all arrayed against Randolph, because he was threatening the Prince with public humiliation. Indeed as you might be able to understand, exposing the Prince was not something done in the Victorian Era, or even at any time since then and even today.

Although Winston Churchill left Dublin and Ireland before he was five, it was Dublin as a city that made a most vivid impression on his mind. He remembers the red-coated soldiers, the emerald grass, the mist and the rain, and the excited and sometimes whispered talk about ‘the wicked Fenians’ who were trying to terrorize the British administration. Once when he was riding a donkey led by his nurse, Mrs Everest, a group of soldiers appeared in the distance. There was a moment of panic as the nurse mistook them for Fenian terrorists; she spooked the donkey who in turn kicked and threw Winston to the ground, which resulted in a slight concussion of the brain for the young lad…

But life in the Vice Regal palace continued as usual with costume and fancy dress balls interrupted by occasional state visits and even more balls of there high society…

Fancy dress was the element that the Churchill’s thrived upon… since both Jennie and Randy, really loved to dress up, and party madly.

On another occasion arrangements were made to take a group of children to the pantomime theatre. When Winston and his ‘woom’ Mrs Everest reached the Castle where they were to meet the others, people with long faces came out and said that the theatre had been burned down, and all that was left of the Manager, they added mournfully” “were the keys that were in his pocket.”

It was right then that Winston asked innocently, and yet eagerly:

“May I see the keys?”

Apparently his request, did not seem to have been well received by his hosts, and they shooed him away, without ever bothering to show him the “keys” in question. It was an unresolved mystery, as to why they were shy about showing him the deceased man’s keys. And at least this is how he describes his first theatre experience many years later when he wrote about it, and about his encounter with the indestructible keys of the Manager…

Winston had plenty of humor as a boy, but he could get away with a fair deal of cynical sarcasm because he looked the very picture of angelic innocence. And because he could contain his mirth and laughter so the unsuspecting victims of his zingers wouldn’t know this is happening.

And if you don’t believe he was an Angel, at least he looked like one…

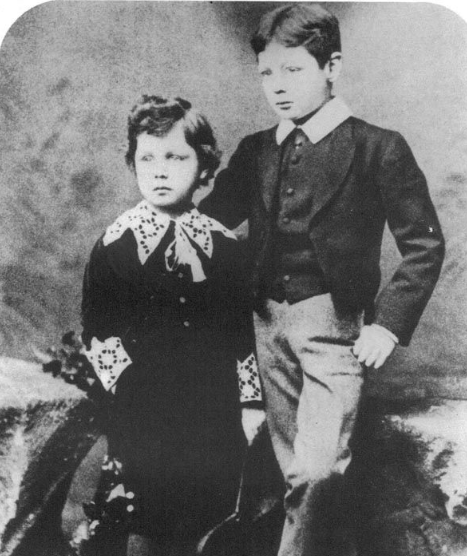

Even the early pictures of Winston Churchill show a pug-nosed, but eerily determined little boy, with a mass of untidy curls, framed by the round sailor hat, that was so dear to the Victorian attitudes towards youth and the sea.

Indeed Winston was red-headed, freckle-faced, and obstreperous red faced boy, and from the moment he learned to talk, he talked incessantly.

Indeed this one thing he did, and perhaps he did it amazingly well.

He talked…

He talked and talked…

And indeed he talked with an unbecoming for his age authoritarian voice, that he had probably emulated from his faux-dad. Randolph, whose stentorian voice boomed across the halls of Parliament, unequalled by anyone else’s volume.

At this time, young Winston offered all his love, all his care, and all his confidence to his governess, Mrs Everest. Mrs Everest much like her namesake, was a towering peak of a woman, and a sweetheart in a large frame for any female. She always smiled and had a happy disposition internally and externally and she loved her small ‘charge’ abundantly. In good turn she was rewarded by an unswerving devotion which lasted until her death; because Winston loved her more than anyone else. That is until he met Clemmie, who was destined to become his wife. Yet all his early life this was Winston Churchill’s ‘Woom’ and none other, for very many years.

He did not see much of his parents. His father was engrossed in Irish politics and his mother caught up in a busy social life. Neither considered children a vocation, and, in the way of most aristocratic families at that time, regarded the nursery, like the kitchen, as necessary adjuncts to thewell-run household, but ones which should be hidden.

Winston admired his own mother from a distance, as if she were a beautiful, far-away evening star.

She obviously had dazzling qualities because people admired her and even wrote lavish praises about her. This is how Jennie Churchill is described by Viscount D’Abernon who wrote of seeing her for the first time at a Dublin Viceroyal ceremonial occasion:

‘I have the clearest recollection of seeing Jennie for the first time’.

‘It was at the Viceregal Lodge at Dublin.’

‘She stood at one side to the left of the entrance.’

‘The Viceroy was on a dais, at the farther end of the room, surrounded by a brilliant staff, but eyes were not turned on him or his consort, but on a dark, lithe figure, standing somewhat apart and appearing to be of another texture to those around her, radiant, translucent, intense.’

‘A diamond star in her hair, her favourite ornament its lustre dimmed by the flashing glory of her eyes. More of the panther than of the woman in her look, but with a cultivated intelligence unknown to the jungle. Her courage not less great than that of her husband fit mother for descendants of the great Duke. With all these attributes of brilliancy such kindliness and high spirits that she was universally popular.’

Her desire to please, her delight in life, and the genuine wish that all should share her joyous faith in it, made her the center of a devoted circle.’

Winston was supremely happy until he was seven years old. His parents moved back to London after their three years in Ireland and he was given a large nursery equipped with all the things that a small boy likes best. He had a thousand tin soldiers, a magic lantern, and a real steam engine. Furthermore, when he was six his mother presented him with a brother, John, whom he regarded as a curious and amusing new toy, if not a fresh possession.

However all good things must come to an end because the following year, some serious adversity set in and disrupted Winston’s merry-go-round life. It was his mother that announced that the time had come for him to go to boarding school. She had selected an expensive, modern school near Ascot which specialized in preparing boys for Eton.

Yet young Winston, dreaded the idea of leaving behind his untrammelled existence under the care of Mrs Everest — and, as things turned out, his worst forebodings were amply fulfilled. Poor lad, he spent two miserable and horrible years at the St. James School, and indeed he hated every minute of these pair of ‘annus horribilis.’

His departure had an almost Dickensian flavour. He was only seven and until then had led a happy and sheltered life. He remembers the ride in the hansom cab with his mother, his growing apprehension, and finally the awful moment when goodbyes had been said and he was left alone with a stern, unbending headmaster. The latter led him to an empty classroom and told him to sit down and learn the First Declension of the Latin word for table, mensa. One can imagine the child’s sinking heart as he looked at

the strange, incomprehensible words. He did as he was bid and memorized them, but when the master returned, inquired boldly:

‘And what does “O-table” mean?’

‘Mensa, “O-table” is the vocative case. You use it in speaking to a table.’

‘But I never do,’ insisted young Winston.

‘If you are impertinent, you will be punished, and punished, let me tell

you, very severely.’ said the master angrily.

This was the beginning of a bad two years for the young and utterly too sarcastic for his age, Winston Churchill.

Discipline at St. James’s was rigidly strict and, according to Winston, the headmaster was cruel and perverted. Apparently the headmaster delighted in assembling the little boys in the library, singling out the culprits one by one and taking them into the next room where he beat them with his cane whip until they bled. The other boys were forced to sit silent and listen to the screams of their schoolmates, trying to keep the triple underwear and the newspapers they stuffed into their pants, from showing…

Of course rather soon, Winston rebelled.

He revolted because he was beaten often and freely, and with such a violence; that Winston declared: “Not even a reformatory school for young thugs, would tolerate such violence against children today.”

Nevertheless young Winston refused to surrender. He refused to write the Latin verses which he declared he could not understand. He refused to curry favour. He refused to repent.

He stayed rebellious, till the bitter end.

He never submitted to the hated Authority figure. Once he even kicked the headmaster’s straw hat to pieces, which made him the hero of the school.

Winston nursed such a grievance against this wicked man, that for years afterwards he brooded on taking some hefty measure of revenge. He planned to return one day, denounce the Headmaster before all his pupils, then subject him to the same punishment he had inflicted on his helpless charges. At the age of nineteen he actually drove to Ascot, but when he reached his destination he found that the school had been abandoned long before, and the hated headmaster had disappeared.

Although Winston’s lion-hearted resistance soon became a legend at St. James school, the frequent corporal punishments, along with the cold baths he was assigned to take as a punishment, undermined his constitution, and his health suffered badly. After two years his family doctor advised Lady Jennie Churchill to remove Winston and take him to Brighton, where he would gain the benefit of sea air, more sun, and certainly far more freedom.

Jennie Churchill listened to the Doctor, and so Winston was soon removed to sunny Brighton on the south west coast. And it was here that his fortunes improved dramatically. Bright as Brighton was how he was soon to be described due to his sunny disposition after he started going to school in Brighton…

He was put under the care of two kind and elderly ladies who encouraged him to study the things he liked, such as English, history, French and poetry. He was also allowed to ride and swim and to read Rider Haggard’s thrilling books King Solomon’s Mines and Allan Quatermain. Other activities included a school paper called ‘The Critic’ in which he lost interest after the first number, and a production of Aladdin which was so ambitious and all encompassing with Winston Churchill as the Director, Producer, and Main Character — that it never saw the light of day…

Yet, at this moment, young Winston Churchill was happy once again, but in all fairness to the masters of St. James’s it must be said that his new freedom, did not bring about any magic change in him as far as obedience, studiousness, or scholarship, were concerned. He had such bounding vitality he could not, it seemed, keep out of mischief. His dancing mistress, Miss Vera Moore, described him thus: “Winston was a small, red-headed pupil, and the naughtiest boy in the class. I actually used to think that he was the naughtiest small boy in the whole world.”

There seemed to be no field in which Winston Churchill’s peculiar brand of cheekiness did not flourish.

Once one of the teachers asked the children to call out the number of good conduct marks they had lost: “Nine” cried Winston, to which the teacher protested: “But you couldn’t have lost nine.” “Nein” repeated Churchill triumphantly: “I am talking German.”

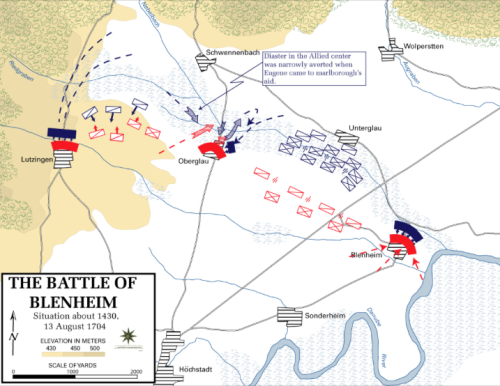

He loved to pull that one prank because he had heard that one of the reasons why his ancestor John Churchill, the Duke of Marlborough had won the European battles that led to the battle of Blenheim and he carried the day there in the field of honor was because he had a superb understanding of the German language and therefore was able to communicate well with all others before, during, and after the battle of Blenheim, since at the time German was the military language of Europe.

He was indeed a handful as a child, and perhaps even more so, as an adult…

Even Winston’s relatives found him a handful. He usually spent his holidays visiting one of his many aunts and uncles, and the occasions rarely passed without some dramatic incident taking place. Sometimes he went to Bournemouth to stay with his father’s sister, Lady Wimborne, and sometimes to Blenheim to stay with his father’s brother, now the

eighth Duke of Marlborough.

Winston loved Blenheim palace because every corner of the resounding halls, and majestic rooms, breathed the splendour of the great defender of the Realm, the ancestral warrior, who had saved England from the rule of a European Tyrant by trashing him in the battle of Blenheim and beyond.

The little boy was dazzled by the uniforms and the armor on display, and by the wonderful trophies, and the battle scenes that adorned the halls, and decorated the walls. But best of all, he loved the toy soldiers that brought to life the armies which his famous ancestor the Duke of Marlborough had commanded winningly in the field of honor.

So to follow in his famous ancestor’s footsteps, Winston Churchill modeled his own collection on this impressive array, and often refought the Battle of Blenheim with himself as the heroic leader.

He replayed this battle, again, and again, and again, until he knew every move. and he could execute every strategy, and every tactic by heart…

He resolved that his life too, would be filled with excitement and glory — hopefully in defense of the Realm, or wherever else he could find his pride and joy; the primordial battle between Good and Evil.

Indeed it would, come to pass some day soon…

Oh Lord, methinks that surely came to pass in ways that none could have imagined at the time of Winston’s childhood epic battles.

And indeed, he never lost his sense for, nor his taste for worthwhile adventure…

Yet back to his growing up, when Lady Jennie Churchill, was abroad, as she frequently was, her elder sister, Lady Leslie had taken young Winston under her wing as part of her brood and he became accustomed to being with her own family.

He became a fixture of her household, so much, that when he was twelve years old, she wrote the following letter to the celebrated author, Mr Rider Haggard: ‘The little boy Winston came here yesterday morning, beseeching me to take him to see you before he returns to school at the end of the month. I don’t wish to bore so busy a man as yourself, but will you, when you have time, please tell me, shall I bring him on Wednesday next, when Mrs Haggard said she would be at home? Or do you prefer settling to come here some afternoon when I could have the boy to meet you? He really is a very interesting being, though temporarily uppish from the restraining parental hand being in Russia.”

Shortly after the meeting Winston wrote to Mr Haggard: ‘Thank you so much for sending me Allan Quatermain; It was so good of you. I like A.Q. better than King Solomon’s Mines; It is more amusing. I hope you will write a good many more books.’

When Winston was not at Bournemouth, or Blenheim, or with Lady Leslie, in her house near Dublin, he sometimes stayed with his mother’s younger sister, Mrs Frewen, in London. And other times the Leslie and Frewen children came to visit him at various houses which Randolph Churchill had rented for the summer. The three Jerome sisters had produced between them six boys and one girl, so there was no shortage of playmates.

A picture taken in 1889 shows Lady Jennie Churchill with her two sons, Winston age fourteen and Jack age eight; Mrs Frewen with Oswald, one, Hugh, six, and Clare, four; and Lady Leslie with Shane, four, and Norman, three.

This were the moments that if one had a time-bending telescope that could look into the future, he could discern that this little boy could conceivably one day become the Champion who saved Christian Western Civilization, from the knell of destruction and death.

Because Winston was always the undisputed leader of the group, being six years older than any of the other children, and his leadership was of a stirring and wilful character. His cousin, Shane Leslie, remembers the agitated consultations between nannies and nursery maids as to how to handle the headstrong boy.

He was the true enfant terrible. Once when he was defying his nurse he searched his brain for something ‘wicked’ with which he could threaten her; finally remembering her strong church principles he declared boldly that if she would not let him have his way he would ‘go and worship idols’.

His cousins regarded Winston with fascination and awe as Shane Leslie said: We thought he was wonderful, because he was always leading us to danger. Sometimes the danger rested in hazardous bird’s-nesting expeditions, sometimes in fights with the village children, sometimes in full-scale battles over carefully built fortresses. Once he even persuaded Mrs Everest to organize an expedition to the Tower of London, so that he could give the younger children a detailed lecture on the tortures used there upon the prisoners who had information to divulge…”

Clare Frewen, who later as Clare Sheridan became widely known as a sculptress and a writer, describes in her memoirs the impression Winston, her cousin made on her: “Winston was a large school boy when I was still in the nursery. He had a disconcerting way of looking at me critically and saying nothing. He filled me with awe. His playroom contained from one end to the other a plank table on trestles, upon which were thousands of lead soldiers arranged for battle. He organized wars. The lead battalions were maneuvered into action, peas and pebbles committed great casualties, forts were stormed, cavalry charged, bridges were destroyed real water tanks engulfed the advancing foe. Altogether it was a most impressive show, and played with an interest that was no ordinary child game.”

“One summer the Churchills rented a small house in the country for the holidays. It was called Banstead. Winston and Jack, his brother, built a log house with the help of the gardener’s children and dug a ditch around it which they contrived to fill with water, and made a drawbridge that really could pull up and down. Here again war proceeded. The fort was stormed. I was hurriedly removed from the scene of action as mud and

stones began to fly with effect. But the incident impressed me, and Winston became a very important person in my estimation.”

During the first three years that Winston was learning at school in Brighton — Lord Randolph Churchill, was moving rapidly towards the glittering height of his political career. Even though Winston was only nine he realized with immense pride that his father was a great national figure. The newspapers were full of his utterances, and the magazines ran dozens of cartoons. He noticed proudly, that strangers even took off their hats when Lord Randolph Churchill passed by, and he heard grown-ups speaking of him as ‘Gladstone’s great adversary. He pored over the daily papers and read every word of his father’s speeches. He bought a scrap-book and pasted in the cartoons. He listened to whatever snatches of political talk he could hear, and acquainted himself with special knowledge of all the great personalities of the day. And, of course, he lined up firmly on his father’s political side…

Anyone who was not interested in politics, he decided, must be very stupid indeed. Once when he visited the Marylebone swimming baths in London he asked the attendant if he were a Liberal or a Conservative: “Oh, I don’t bother myself about politics” replied the man. “What” gasped Winston in indignation: “You pay taxes, and you don’t bother yourself about politics? You ought to want to stand on a box in Hyde Park and tell people things.”

On another occasion Winston refused to play with a certain friend anymore, and when the friend’s father inquired why, the boy answered: “Winston says you’re one of those damned Radicals and he’s not coming over here again.”

Lord Randolph was apparently unaware that he had such a staunch supporter in his elder son. He was completely centered in his own affairs and spared little time for his children. They were almost like strangers to him and yet when Winston was thirteen his father introduced him to Bram Stoker, the author of Dracula, saying: “He’s not much yet, but he’s a good ‘un.'” Winston was enormously pleased by this tribute but during the next

few years was doomed to fall considerably in his father’s estimation.

The trouble, once again, was school; and this time it was Harrow. From the very first he was a failure. Most members of the Churchill family went to Eton, but since Winston had suffered from pneumonia twice, his mother decided to send him to Harrow which, since it stands on a hill, was supposed to be healthier for a boy with a ‘weak chest.’ The Latin entrance examination paper which Winston handed in, however, contained nothing more than a figure one in brackets, two smudges and a blot. However, Dr. Welldon, the Headmaster, took the unusual step of examining his other papers himself, and being convinced that it was impossible for Lord Randolph’s son to be totally devoid of intelligence, persuaded himself that they showed traces of originality.

On the strength of his intervention — Winston was admitted to Harrow as a fresher…

Things went from bad to worse. Winston passed into Harrow the lowest boy, in the lowest form, and he never moved out of the Lower School, the whole five years he was there. Roll call was taken on the steps outside the Old School and the boys used to file past according to their scholastic record. Although in 1888 Lord Randolph was out of office he was still a world figure and sometimes visitors gathered to catch a glimpse

of the brilliant mans’ son. Winston often heard them exclaim in amazement: ‘Why, he’s the last of all!’

Surely still recalling the daily humiliation, Winston many years later proclaimed firmly:

“I am all for the Public Schools but I do not want to go there again.”

Indeed the Headmasters also struggled with Churchill whose antics left them in a daily panic of quandary on how to handle this “wild one,” if not full of bewilderment, and indignation because Winston was full of self-confidence and assertiveness. At the time, young Winston could talk Arabs out of their camels, and Eskimos out of their fleece. So indeed why could he not learn the rudiments of Latin and Mathematics was a major question tantalizing his teachers. Yet to this day Winston Churchill insists that where “my reason, imagination or interest was not engaged I could not or would not learn.”

There is no doubt that stubbornness played a considerable part, because when his twelve years of school came to an end, he declared with some pride that no one had ever succeeded in making him write a Latin verse or learn any Greek except the alphabet and Homer’s Odyssey & Iliad.

Regardless of his Homeric inklings, Winston as result of his carefully curated selection of personal interest subjects — he remained perpetually at the bottom of the class; and as a

further result he was thoroughly grounded in English. If he was too stupid to learn Latin he could at least learn English. He was drilled over and over again in parsing and syntax. He writes: “Thus I got into my bones the essential structure of the ordinary British sentence which is a noble thing. And when in after years my schoolfellows who had won prizes and distinction for writing such beautiful Latin poetry and pithy Greek epigrams had to come down again to common English, to earn their living or make their way, I did not feel myself at any disadvantage.”

Churchill loved to experiment with the use of words and was passionately fond of declaiming his hastily improvised or made-up speeches in a rhetorical or impassioned way to any impromptu or inopportune audience. He astonished the School Headmaster, Dr Welldon, by reciting twelve hundred lines of Macaulay’s ‘Lays of Ancient Rome’ without making a single mistake. A singular feat for which he won a school prize. The Headmaster Dr Welldon thereafter always declared: “I do not believe I have ever seen in a boy, such a strong veneration of the English language.”

Other worthy testimony for the young pupil, comes from Mr Moore, who ran the Bookshop at the Harrow School: “Winston Churchill … in his schooldays already showed evidences of his unusual command of words. He would argue in the shop on any subject, and, as a result of this, he was, I am afraid, often left in sole possession of the floor.”

Churchill was no better at sport than he was at Latin or Greek. He hated cricket and football and the only distinction he won was the Public Schools Fencing Competition. He was not a popular boy. Instead of being subdued by his failures he grew more self assertive than ever. Once he crept-up behind a small boy standing on the edge of the swimming pool and pushed him in. As the dripping and indignant figure climbed out, some of the boys who had watched the incident chanted with delight, ‘You’re in for it,’ for the victim was none other than Leo Amery, a Sixth Form boy, who was not only Head of his House but a champion at gym. When Winston realized the full implications of his act he went up and apologized. ‘I mistook you for a Fourth Form boy,’ he explained, ‘you are so small.’ Then, sensing that this had not improved matters, added quickly: ‘My father too is small and he also is a great man.’ Leo Amery, who in later years sat in many of the same Cabinets with Churchill, burst into laughter and warned the miscreant to be more careful in the future.

Amery got his own back on Winston a short time later when the latter wrote several letters to the school magazine criticizing the gym. Amery was one of the schoolboy editors, and when Winston Churchill’s second contribution was sent in, containing an even more spirited attack than the first, he wielded the blue pencil firmly. With tears in his eyes Winston remonstrated that Amery was deleting his best paragraphs, but the latter was adamant and the letter was published with the following footnote: We have omitted a portion of our correspondent’s letter, which seemed to us to exceed the limits of fair criticism.

Winston Churchill’s letters were published under the pen-name, Junius Junior, and even with the editorial excisions, corrections, and omissions — Headmaster Welldon felt that Winston was going too far. He summoned him and said that he had noticed certain articles of a subversive character critical of the constituted authorities of the school; that as the articles were anonymous he would not dream of asking who wrote them, but that if any more of the same sort appeared it might be his painful duty to ‘swish’ Winston Churchill.

Churchill, however, was not intimidated by a dressing-down. Mr Tomlin, who was the Head of School in Winston’s second year, wrote: “When Dr Welldon once had Winston ‘on the carpet’ and said, ‘Churchill, I have very grave reason to be displeased with you,’ the boy retorted brightly, ‘And I, sir, have very grave reason to be displeased with you.’

Despite Winston’s sauce, Welldon confided to a friend that he was one of his favourite pupils.

Winston Churchill’s literary efforts did not extend much further than his attacks on the gym, save for a long poem on an epidemic of influenza. One of the verses went:

“And now Europe groans aloud

And ‘neath the heavy thunder-cloud

Hushed is both song and dance;

The germs of illness wend their way

To westward each succeeding day

And enter merry France.”

Churchill did not worry about his unpopularity with his schoolmates, for he was not a boy who feared to be alone, since he could always find something amusing to do with his leisure. When he was fifteen he made an experiment which fortunately escaped the notice of the masters. In the town of Harrow there stood an old deserted house with a large garden. As the building fell into decay it became known as ‘The Haunted House.’

There was an old well in the garden and people claimed that a passage at the bottom led to the Parish Church. Winston thought it would be fun to find out whether this was true and hit upon the happy idea of blowing it up.

With some gunpowder, a stone ginger-beer bottle and a homemade fuse, he assembled an elementary but effective bomb, and placed it at the bottom of the well. Nothing happened and he leaned over the wall.. to check & see: “At that moment the bomb exploded. Winston was not hurt but his face was blackened and his hair and eyebrows singed. The neighbours hurried to their windows and a Mr Harry Woodbridge, who lived in Harrow, declared that his aunt ran out to help the boy. She brought him into the kitchen and bathed his face. When he left he thanked her and said: “I expect this will get me the bag.” But the Harrow School Headmasters did not hear of the incident and Winston’s fears and perhaps secret wishes for expulsion — sadly were not realized.”

Winston’s indifference to his schoolmates probably revealed itself most nobly in his attitude to the devoted Mrs Everest. English Public Schools are cruelly critical of the outward display of affection, and for this reason boys have even been known to beg their parents to keep away. Winston not only invited Mrs Everest to visit him but when she arrived, enormously fat and smiling, kissed her in front of all the boys and walked down

the street with her arm in arm. Jack Seely, an old Harrovian who afterwards became one of Winston Churchill’s Cabinet colleagues, and won the D.S.O. in the First War, witnessed the incident and described it as one of the ‘bravest acts’ he had ever seen.

Back in London, Jennie and Lord Randolph were at turns, startled and worried by their son’s scholastic failures. They must have felt that the boy must be somewhat backward and for the first time began to concern themselves about his future. Occasionally Randolph, visited Winston at Harrow and followed the approved pattern of parental behaviour by taking him and his school friend, Jack Milbanke, to luncheon at the King’s Head Hotel. Winston sat awkward and silent, listening to Milbanke conversing so easily with his brilliant father and wishing with all his heart that he could do the same. But Lord Randolph intimidated his son. He was remote and impersonal and even then made no effort to gain his confidence. The son was filled with admiration for his father, yet in his presence was always remaining quiet, gauche, and self-conscious.

In due form though, we should record what transpired before he was able to join the Royal Military Academy at Sandhurst, because Winston Churchill had to overcome some serious adversity, as always, he had to do before any of his great Victories. He had to taste the bitter pill of defeat before Lady Fortune smiled upon him. Same as here, when just before Winston Churchill passed his final examination for the Royal Military Academy of Sandhurst — he had a serious accident: “He went to visit his aunt, Lady Wimborne, at Bournemouth. He was being chased by his cousin and his brother and suddenly found himself cornered on a bridge, under which lay a ravine covered with pine trees. He rashly decided to avoid capture by jumping into the ravine, hoping that the trees would break his fall and deposit him on the earth unhurt. His plan misfired and he fell twenty-nine feet onto hard ground. The two boys ran into the house and fetched Lady Randolph, saying: ‘Winston jumped over the bridge and he won’t speak to us.’

For three days he was unconscious. His father hurried from Ireland and all the most eminent specialists of the day were summoned. He had a ruptured kidney which called for an immediate operation. The news went round the Carlton Club that Lord Randolph’s son had met with a serious accident playing ‘Follow my Leader’, to which the wits replied: ‘Lord Randolph will never come to grief that way.’

Winston was laid up for nearly the whole of the year 1893. But his convalescence, far from proving dull, opened up for him the exciting world of politics that he had hitherto only read about. His parents took him to London where they were living with his grandmother, the dowager Duchess of Marlborough, at 50 Grosvenor Square. Lord Randolph Churchill was a sick man; he was shrunken and pale and had grown an enormous, shaggy beard that seemed to accentuate his illness. Yet he still dreamed of retrieving his position, because he felt he had been badly used; and Winston had heard him refer bitterly to the Tories as “a Government and a party which for five years have boycotted and slandered me.” He had therefore gained a certain amount of satisfaction when, a few months previously, Gladstone had beaten the Tories at the polls and ascended the throne once again.

Lord Randolph’s sister was married to Lord Tweedmouth, Gladstone’s chief whip, so the Churchills found themselves in the Liberals’ inner circle. Every day there were people for lunch and dinner and here the eighteen-year-old Winston met for the first time many of the great figures whom he was destined to know as colleagues in the days to come. He met Mr Chamberlain, Mr Balfour, Mr Edward Carson, Mr Asquith, Mr John Morley, Lord Rosebery and many others. He often attended the House of Commons, and heard Gladstone wind up the Third Reading of the Home Rule Bill. One evening when Edward Carson came to dinner and discovered that Winston had spent the afternoon in the gallery, he said: ‘What did you think of my speech?’ Young Winston Churchill, replied solemnly: “I concluded from it sir, that the ship of State is struggling in heavy seas.”

What fascinated Winston most about the House of Commons was that although the battle across the floor was sharp and fierce, when opponents met outside the Chamber they were friendly and courteous. On one occasion he heard his father and Sir William Harcourt exchanging very acrimonious charges. Sir William seemed to him unnecessarily angry and extremely unfair. He was therefore astonished when the latter came up to him in the gallery, shook his hand and smiled and asked him what he

thought of the speech. The lack of rancour impressed Winston. It was the truly sporting way to fight, he decided, as chivalrous as the knights of old; and it is worth noticing that he has always modelled his own conduct on these Victorian examples.

As the days passed he tried eagerly to draw closer to his estranged and always distant family father, Lord Randolph Churchill, without much success…

Yet he kept on trying, because a short time before his accident he had caught one fleeting glimpse of the inner man, which encouraged him and filled him with hope. He had let off a gun at a rabbit which happened to appear on the lawn just below Lord Randolph’s window. The latter spoke to his son angrily, then suddenly melted. He talked gently about school and the Army, and the difficulties and rewards of life in general. At the end he said: “Remember things do not always go right with me. My every action is misjudged and every word distorted. … So make some allowances.”

The fact that Lord Randolph had opened up to his erstwhile ‘son’ for these few minutes filled Winston with hope, that he can chisel away at the stone faced moment to get some inner warmth and humanity towards his distant and strange father, whom he truly loved, defended, and respected truly, and always.

He thought that perhaps one day, when he had made his name and fortune, he would enter the House at his father’s side and they would fight their way together. But this one ‘father to son’ ‘talk’ was the only intimate conversation Winston was ever going to have with Lord Randolph Churchill…

Strange indeed…

Another day when Winston was fourteen and staying at home on holiday; Lord Randolph went up to the nursery, and he found Winston replaying with his soldiers which were then over fifteen hundred strong, the epic battle of Blenheim. Randolph studied the battle arrayed as the lead soldiers stood ready in the proper line of battle and after some thought, asked him if he would like to become a soldier. Winston was instantly delighted to think that his father had discovered in him the seeds of military genius. What he failed to realize for many years, as he later said; was that Lord Randolph had decided that “soldiering” was the only career for a boy of limited intelligence, such as this one who preferred to play with his toy soldiers all day long…

Yet, Winston was immensely pleased at the prospect of a military life and career. He immediately took a special course at Harrow to prepare him for his Sandhurst entrance examination, but even here he did not succeed.

Twice he took the examination and twice he failed.

In exasperation his father removed him from Harrow and sent him to a “crammer” to school him in preparation for the admittance examination for Sandhurst. After the requisite preparations, Winston took the examination for the third time, and passed. But so came in so low that he was not qualified to enter any regiment, but the cavalry. The cavalry accepted a lower standard since its primary requisite was for young men of independent means who could and would pay for their own horses, uniforms, and upkeep…

When Lord Randolph heard of what he saw as his son’s latest “failure” he was very angry indeed, and wrote him a terse letter warning him that if he did not pull himself together he would become a “social wastrel” for the rest of his life. Because Lord Randolph had set his heart on Winston’s joining the 6oth Rifles — he now had the humiliating duty of writing to the Colonel of the Regiment, and explaining that his son was “too stupid” to qualify for the 60th Rifles Regiment, and instead had joined the cavalry…

Yet all was well, because and probably despite his father’s indignation; Winston was thrilled at the thought of becoming a smart cavalry officer.

He reckoned: “Riding is more fun than walking.” He thus entered the Royal Military Academy, with a light heart, a sure smile, a great uniform, a shining sword, a side arm, and a swift tempered white horse.

What’s not to like?

He was in Heaven.

Life was suddenly sweet for young Winston Churchill.

Now he said: “Let the games of war, life, and polo begin.”

Leave a comment